Harvest journal: making soap

I read cookbooks for fun. My fascination with cookbooks began when one of my professors mentioned reading one from ancient Egypt. How recipes are written varies by culture. One of my all time favorites is Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. What she provides in that one book is technique. One such gem of process is how to render fat. She was speaking in terms of rendering duck skin, which produces these wonderful morsels of duck chicharones as well as duck lard. I use the same method to transform venison suet into venison lard.

Why would anyone want to render venison suet? The lard, paired with other fats (including duck lard!) makes wonderful soap. Michael started making soap decades ago due to my allergies to commercial scents. At one point, we could not find unscented soap. His first efforts involved shortening and olive oil and drain cleaner. He has since found a more reliable source for lye and our access to suet sources reduces the cost of the soap. My skin loves it!

Deer store fat in layers on their rumps, chest, and in their abdomens. Unlike beef, it doesn’t marble the meat. It is really easy to peel off the fat during venison processing. At that point, I put it in a separate bowl and when I’m ready to render, chop it into cubes.

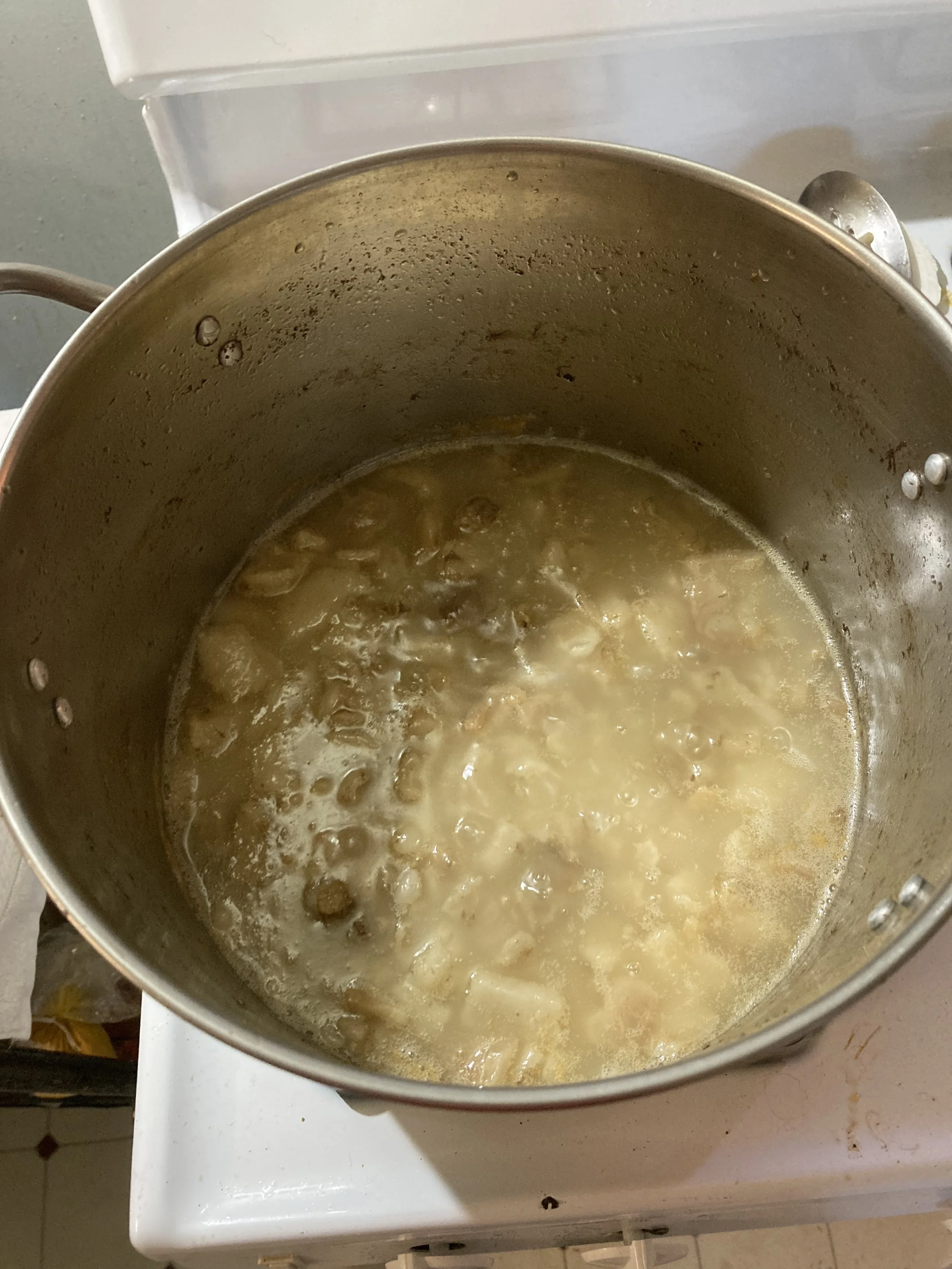

The cubes go into a large stock pot, with enough water to barely cover them.

You bring the water to a simmer, leaving the pot uncovered. The target is to allow the suet to soften and release those fat molecules from the tissue. The milky hue of the liquid means it still contains water. By the way, this process smells wonderful in a fried meat kind of way.

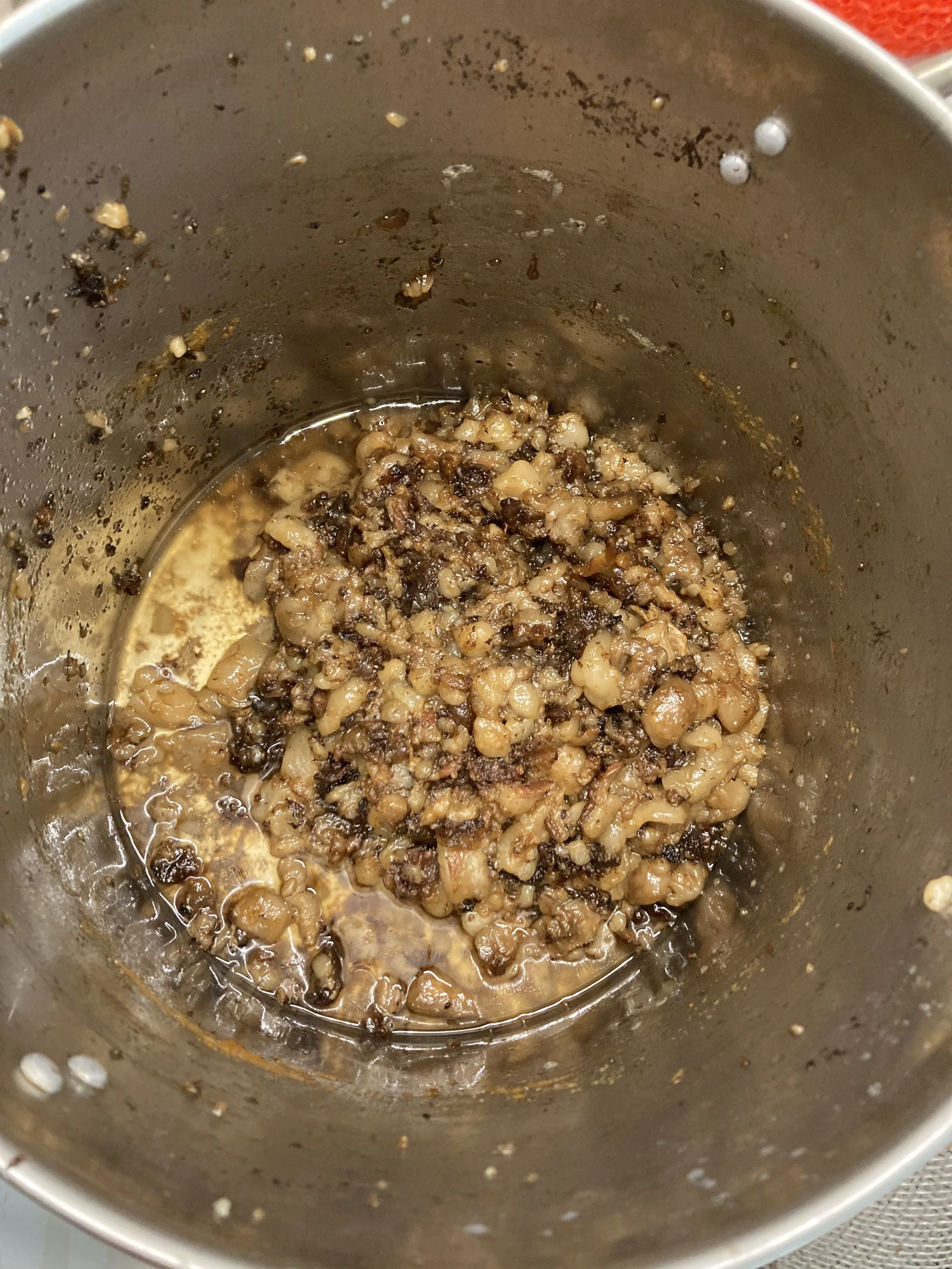

I forgot to take a photo before I started to separate the cracklings from the lard, but you can still see that the liquid graduates from milky to clear.

I strain the rendered fat through a wire mesh colander and feed the cracklings to the birds. Pheasants love it.

The lard turns opaque as it cools. I use a glass mixing bowl and put it outside to harden. When Michael is ready to make soap, he brings in the bowl and the fat separates from the glass due to differential shrinkage rates. Otherwise it’s hard to get it out of the bowl. He scrapes off any fried bits that made it through the strainer. They tend to congregate at the bottom for easy separation.

Seventeen pounds of soap may get us through to next year, depending on how much we give away.

We have all these delicate little bodies to keep clean and happy.